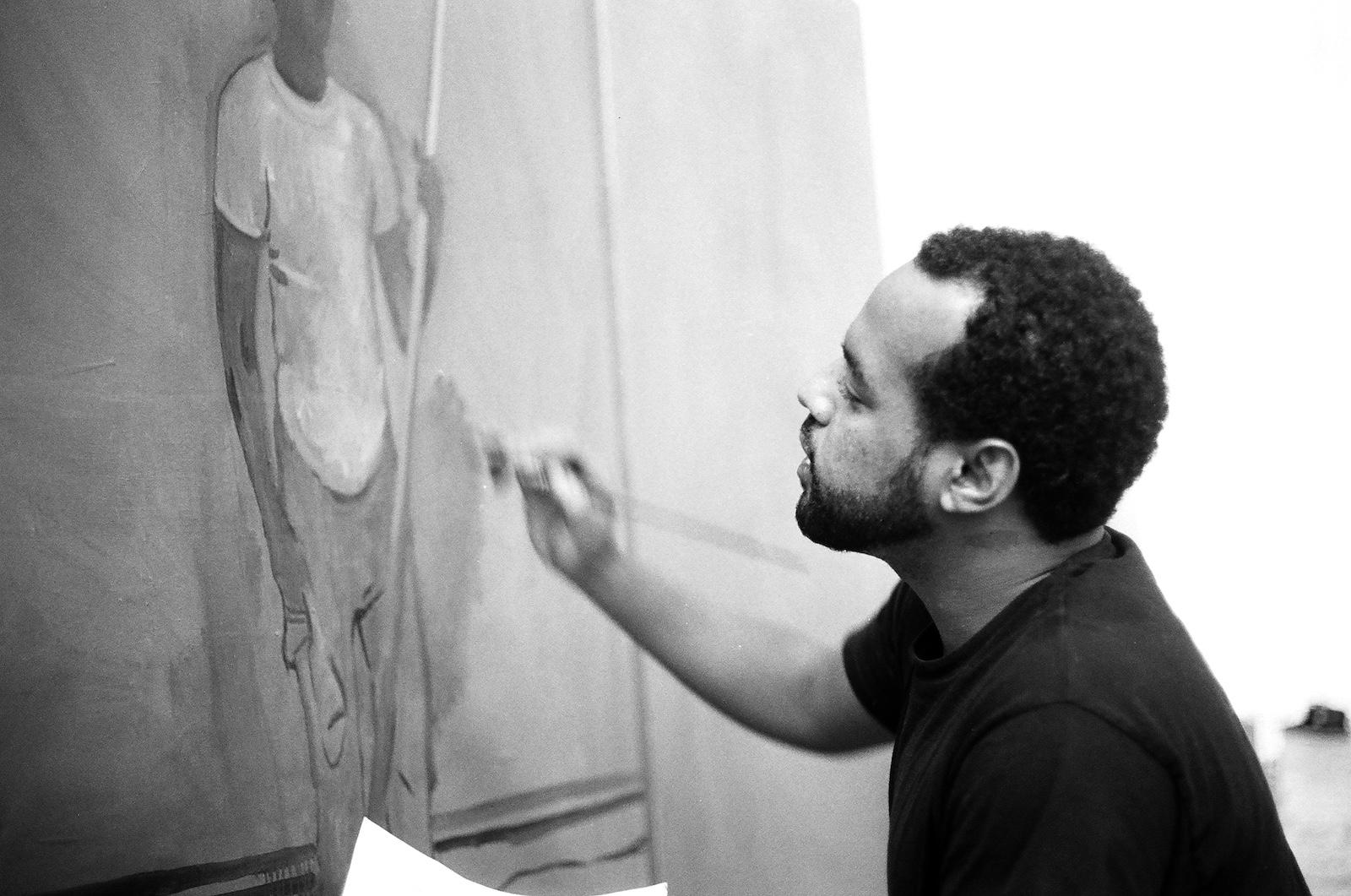

Presented chronologically, the show’s first gallery features pictures of random strangers sourced from old photos. “When I first started painting, I wanted to paint these anonymous moments and make them permanent,” he says. “I was going to swap meets, and they had these photo bins, and there are thousands and thousands of photographs that are just anonymous.”

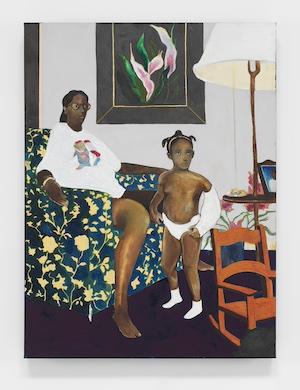

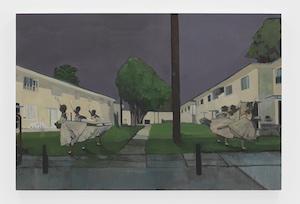

A scrappy Cooper Union dropout and former MOCA bookstore clerk, he depicts quotidian moments in paintings like “Single Mother with Father out of the Picture”, a girl with a cast on her arm next to her mom on the couch, and “Bad Boy for Life”, a woman spanking a boy bent over her lap.

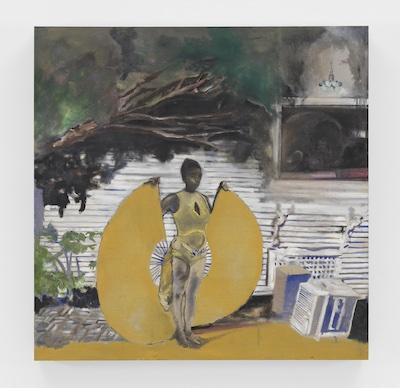

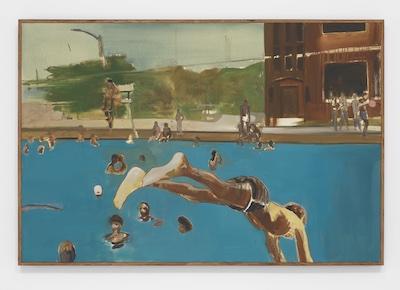

“You rarely see Black people represented independent of the civil rights issues or social problems that go on in the States. I’m looking to move on from that stage,” he says in the catalog that accompanies the show. In the film, he elaborates, “I wanted to make something that was extremely normal. I want Black people to be normal, that was my goal. We are normal, right? But I want it to be more magical. I don't want it to be stuck in the alley.”

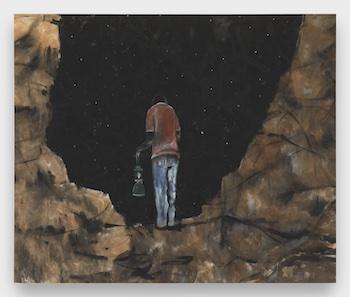

Magic features in paintings like “40 Acres and a Unicorn”, a boy riding the mythical beast, set against an all-black background. Bleakness presides, perhaps commenting on the Reconstruction measure guaranteeing 40 acres and a mule to freed slaves, a promise unfulfilled under Jim Crow. The same bleakness persists throughout the show– facial features blurred, often nightmarishly so, as in the works of Francis Bacon, an influence.