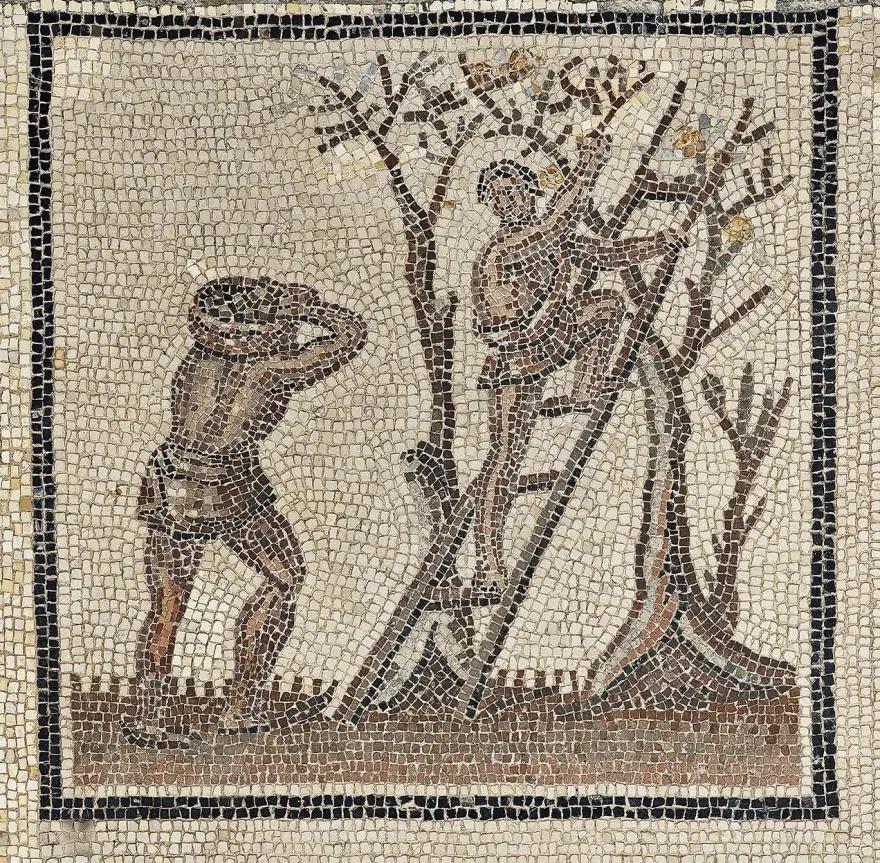

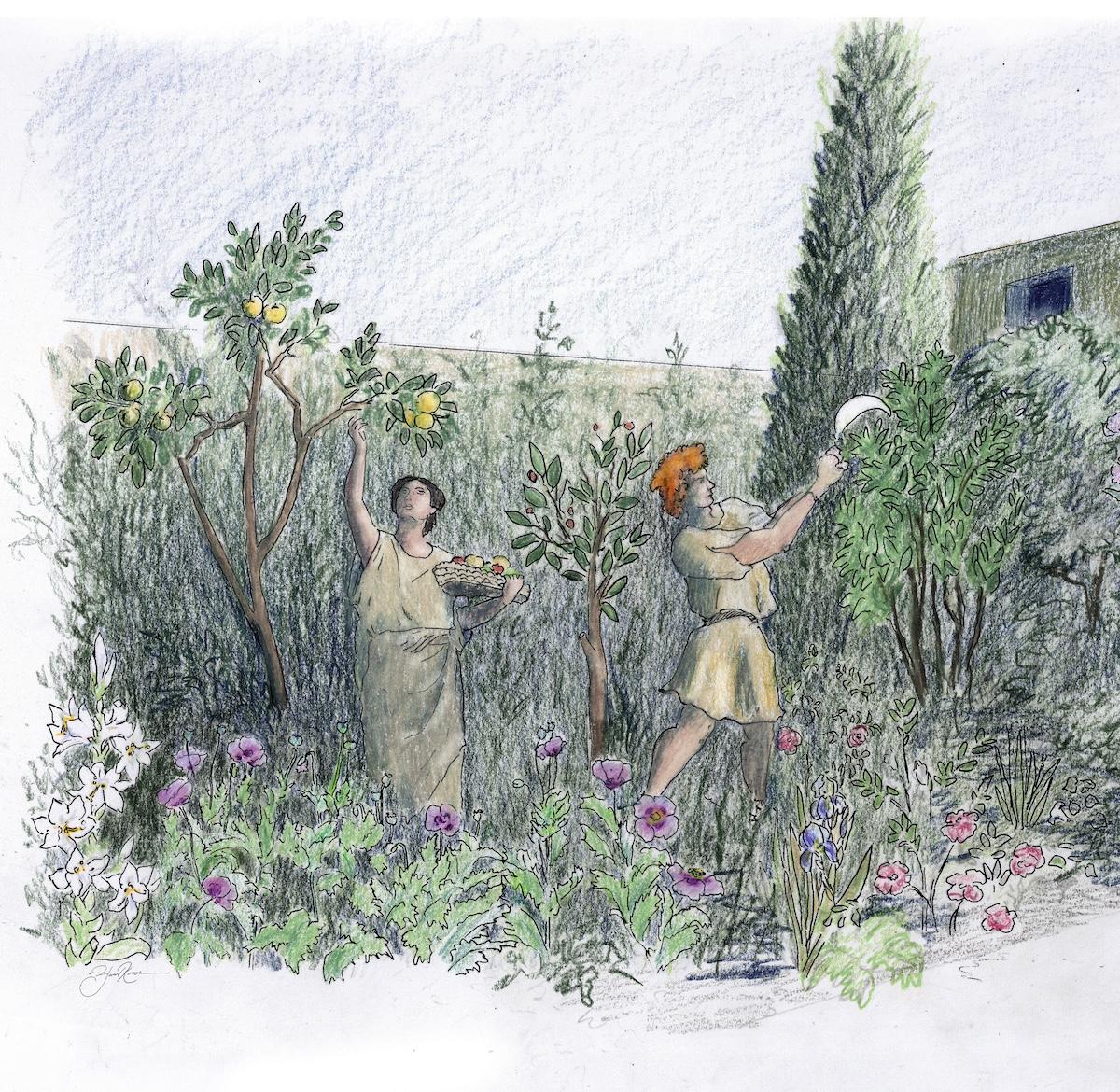

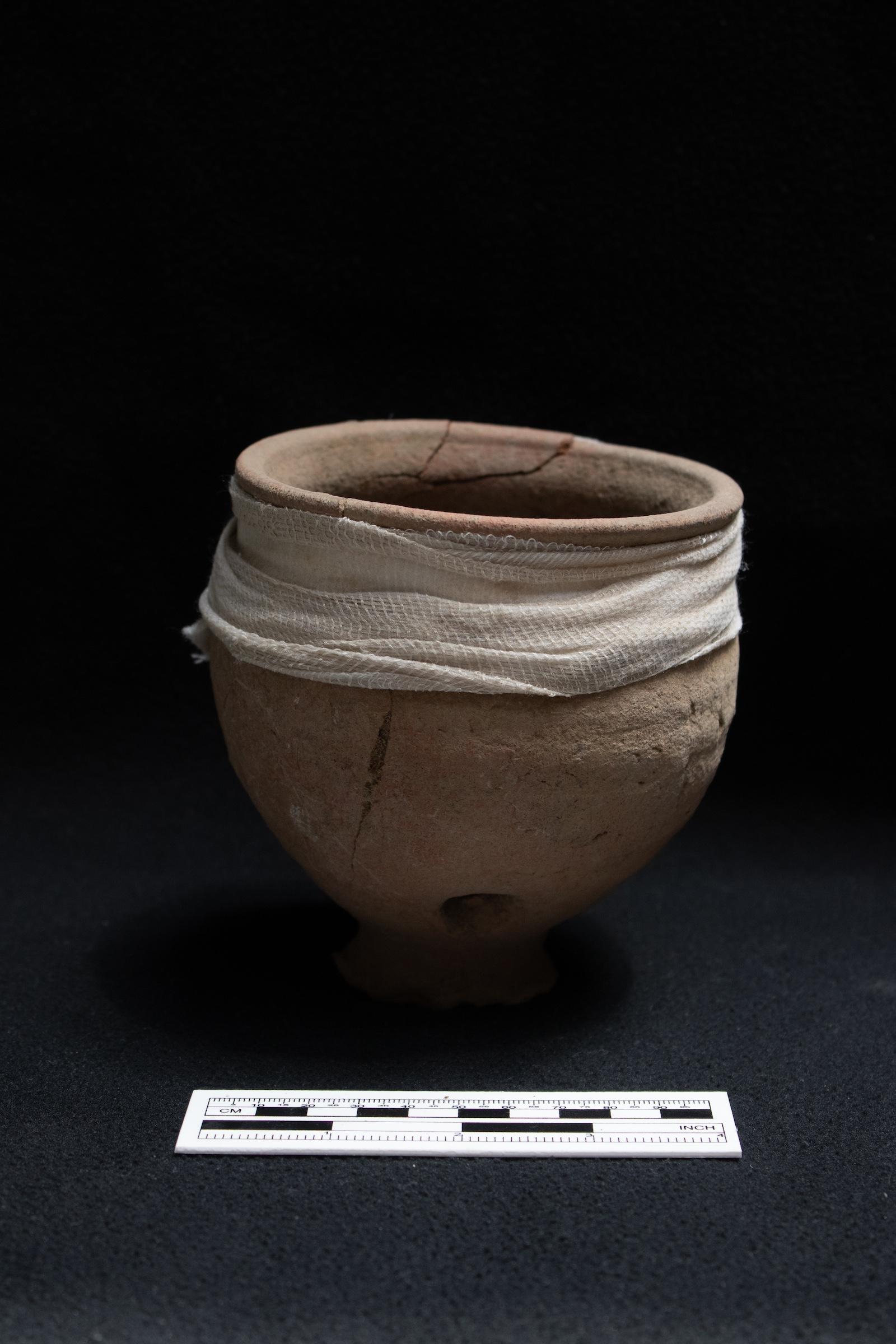

Dr. Feito recreates these activity pathways by examining soil from the excavated garden layers through a process called flotation wherein sampled soil is poured into a multi-chamber water reservoir or simply a bucket. Heavier soil particles sink to the bottom of the reservoir, and lighter plant materials float to the top and down into a collection screen. From there, they are dried, analyzed, and categorized. In this way, Dr. Feito can identify what plants and plant families are represented in the garden soil and how they were preserved. The presence of certain plants and the means of their depositions allow the reconstruction of the past “human-environment interactions” that interest both Dr. Feito and Dr. Tally-Schumacher.

For Dr. Feito, one of her main interests concerns plants as food and markers of cultural change. “Plants are fundamental here,” says Dr. Feito. “They’re the center of not only the diet but the economy. Food is at once individual and universal. People express their identities with food, but they also have to eat. It is also something subject to trends and changes and, particularly in the ancient world, when people come into contact with new populations, you see the introduction of new seeds, food plants, and eating patterns. You can literally see evidence in the archaeobotanical record of cultural contact.”