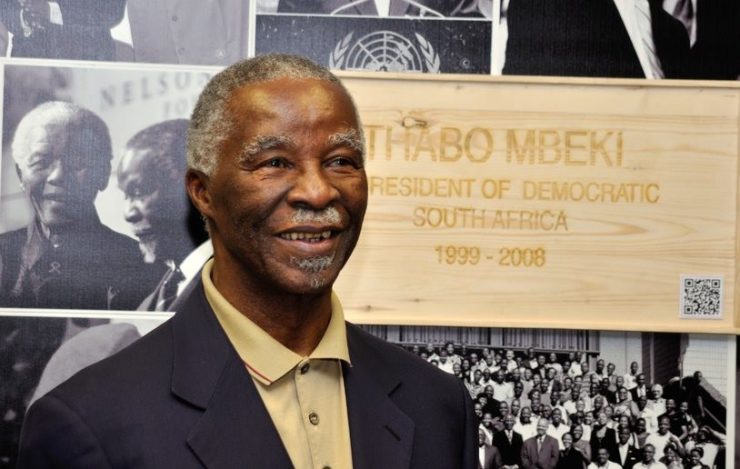

A CONVERSATION WITH PRESIDENT THABO MBEKI, PART 2

This is the first interview report with President Mbeki on June 19, 2022. Viewership figures on television, radios and over a dozen platforms reached over 35 million by June 20, 2022. For the transcripts: YouTube: https://youtube.com/watch?v=KoRTpv6lEfA Facebook: https://fb.watch/dL9miB2tHc/

Thabo Mbeki: South Africa and Its Challenges

Toyin Falola

Ideas rule the world, and no matter the level of modernity associated with a nation, ideas are the bedrock of such modernity. Despite the conventional understanding that ideas are crucial to enhancing developmental initiatives, innovations and inventions, they usually emanate from the pool of thoughts and mental gymnastics carried out by certain individuals and codified in some accessible materials. Humans have done exceptionally well from one generation to another, not strictly because they have leapfrogged the numerous accomplishments, progress, and success that have been achieved hitherto but because they can consolidate on previous successes.

To this extent, as people, we are who we are because we mostly depend on the success of preceding generations while trying to make sense of the complex and complicated world they found themselves in. How people access these ideas is the most logical question that anyone should ask since it is improper to allow our contemporary familiarity with various agencies of information preservation and dissemination to deny us the honour of acknowledging that accessing information has not always been an easy task. For a long time, these pieces of useful information were stored in the oral archive of the people, especially in Africa.

In essence, the younger generations only have access to their predecessors’ beautiful ideas by listening to talks and stories from the elderly, who are considered the living library of the civilisation. These stories are usually accompanied by evidence of success in innovations associated with these past individuals. However, there is a more important agency of all the information coded by people in our current world. And that is the book. Books are hard and sometimes soft materials that record ideas in writing forms. Thus, people access books to get important information, especially about what the books promise to offer on particular subjects. For instance, people who want knowledge about how political science and world experiences have been from time immemorial would not look in books written by medical professionals whose subject matter is endoscopy. Technically, anyone reading a book is consulting others; therefore, books are written with a specific audience. An important advantage of reading is that it does not limit an individual on what they decide to achieve with their lives from the ideas gathered from reading and consulting.

In our recent world and collective history, individuals are shaped by the number of ideas they have access to through reading, and Thabo Mbeki is living evidence. A one-time President of South Africa, Mbeki has experienced geometric success as a political figure in the continent, banking on the strong foundation he had built as a child. The culture of reading was imparted to him by his well-versed parents, which introduced him to ideas and ideals, issues and values that he inculcated as a child growing up in politically convoluted South Africa. The importance of getting used to books is undeniable, as this tradition introduced Mbeki to the fact that a leader who would make a maximum impact has garnered different amounts of useful information in the course of reading.

Records abound that Thabo Mbeki was very successful in the South African political arena, specifically and in Africa, because he championed the act of distributive leadership and purposeful representation while in office as President. But then, South Africa is a country that has a deep-seated history of political problems engineered by the fact of colonisation and apartheid. Of course, every African country, especially the colonised ones, faced and still faces the backlog of challenges inherited from their imperial invaders who doctored the institutions to ultimately satisfy the whims and caprices of their imperialist aspirations. However, the issue of South Africa is different, almost in character and operationality, for colonisation attained a different height of dehumanising experience that would haunt the aborigines of the place for a long time. We must clarify that their problems are aggravated by the unholy colouration or imperialism that brought apartheid and its many indignities.

To a considerable length, colonisation can be excused by those who engaged in the exercise of domination on the account that humans in different parts of the world always nurse the ambition to lord over others, using their advantages as the instrument of subordination and destruction. While that is a general thing, what is not general and deserves to be carefully considered is the manufacturing of hate on creatures of the same species for no particular reason but their skin colour. The hatred of human beings constitutes the raw description of what Frantz Fanon called “othering.” The South African people were conceived as an impossible creation that did not merit a slot in the community of humans because they were regarded as inferiors by the European imperialists.

Given the predatory ambition to encroach on the natural and, by extension, human resources of the people in that geographical space, associating less than human qualities with the people aggravated their relationship in every ramification. Colonised people were theoretically or ideologically seen as a group whose assumed primitivism warranted some immediate humanitarian ambition to save them from themselves. Based on this assumption, they needed to establish that the moral reason for colonisation was because the indigenous people were mentally inferior, justifying the imposition of the West on them to run their government and overtake the economies linked to that government. However, the desire to establish such apartheid systems is underscored by a more benightedly beguiling mindset founded on a philosophy that anyone who looks different does not deserve to be treated decently. Coupled with the seizure of power through the forceful imposition of government on them, using guns and other sophisticated technologies, the South African people became helpless in the hands of their oppressors, who appeared to have come to displace them from their ancestral homeland. This continued for a protracted period, but the people endured.

Confronting the aborigines of South Africa are the combined compulsive problems of self-hate, identity politics, epistemicide, and political hara-kiri, all of which somnambulate them for a very long time. Living for centuries with dignity, they did not experience such hateful relationships occasioned by their skin colour. The most basic question many South African under apartheid asked themselves was if truly they were humans. This question was unavoidable, especially with the idea that humans’ genetic neighbours, the chimpanzees and their kindreds, when seen, are treated in the same way to send a message that even though humans share a compelling similarity in their composition, they have a different sense of development. Therefore, many South Africans were justified to rethink their identity and meditate if they truly were in the same category as these whites. If they were doubtful of this reality, the common fact that the white exhibited similar characteristics was an indication that they were both in the same human category. Therefore, the need to rapidly disengage and dissociate from the actions leading to their treatment came from their inferiority complex.

South Africa’s problems do not mandate a quick fix, no matter how much the people anticipate developmental changes. Thabo Mbeki tenaciously believes that the foundation of any form of change that would be erected should be based on communication, which is a viable and vital solution to the myriad of problems that confront the country. This is underscored by the understanding that for people who have undergone that painful process of self-abnegation and integrity erosion, there is the need for the restoration of sanity first before any other thing. Thus, they must be communicated with by governments representing their skin colour and by people from the same racial circle so that they would immediately begin to unwrite the series of self-hate inscriptions that they have carved in their minds. They must be communicated with the immense greatness that lurks in their skin and the almost inexhaustible potential they carry as Black people. Meanwhile, the agencies for passing this communication are numerous. While they can be communicated with in speech situations, Mbeki believes that the generationally haunted South Africans can be communicated with through other effective means that are specifically highlighted in this great interview.

Photo: Nelson Mandela and Thabo Mbeki (Source: SowetanLIVE)

Establishing credible institutions that would re-engineer fairness and justice in the relationship between classes of people in the South African society is the first indication of communication dissemination to the people of the new dawn and the beginning of a different socio-political condition that gives them back the power to exist as humans. Institutional development is necessary as the first instance of communication between a messianic government in South Africa and the haunted ones because apartheid and its racial inclinations were built through these institutions. With a racialised bureaucracy, many indigenous South Africans could not have access to jobs that could put food on their table. They could not secure employment that matched their human status, apparently caused by the narcissistic evaluation of their skin. As earlier stated, the colonial imperialists assumed that people with a skin of their type did not deserve a decent lifestyle, which was the foundation of the woes that consumed the South African.

In essence, the older system that took away their food and means of survival would take a different outlook on communicating based on the new system of power. It is necessary to consolidate this communication strategy in other areas of the country’s leadership, as that would restore sanity. It is a commonplace that the victims of colonisation are being denigrated on account of the political systems they operated on before the invasion of the colonial power. The understanding that people were colonised is hinged on the assumption that they have inferior systems, including their system of government. To this extent, the poor colonial subjects were mesmerised and ridiculed by an inordinate system of government imposed on them by those who would later speak of democracy.

Although it would later be discovered that democracy was a reasonably fair system of political engagements, the fact that the oppressors did not embrace it during apartheid indicates that they were diabolical and unreliable. Even if the new government installed by the people would embrace democracy as a system of governance, it goes without saying that the colour of South Africa’s democracy would be different for reasons not unconnected to the post-apartheid realities. For one, the invading colonisers were not reneging on the aspirations to remain in South Africa, which would create difficulty as it is ideologically difficult for them to live in genuine peace with the people against whom they have violated their fundamental human rights.

In all of these complex interplay of democratic culture, which was expected to stand erect in the new South African environment, with the emotionally belaboured population that has witnessed a series of negative experiences that have damaged their psyche, one would genuinely ask what the takeaway, the moment of joy, and the course for happiness in the lives of the South Africans will look like. To the once tormented citizens of South Africa, the most important thing is that even with the overwhelming totalitarian values imposed on them and the overweening character of these invaders, they were able to grind their ways until they become liberated. Freedom, it appears, can be underrated when nothing has ever come to threaten it. Humans who have not experienced physical or emotional confinement would find it difficult to understand what it means to access freedom as their social and fundamental right. They often assume that their ability to work in places and, in some cases, decide on who they associate with comes with being free. For example, not many South Africans would say they experienced freedom under the European systems. Apart from being challenged to re-engineer their social and cultural behaviour based on the ideas that they would shift for the white in the country to rule, they were confronted with the challenge of being mentally sane under a government that continues to frustrate their mental health.

In essence, what was important to them was the sound of liberation successfully fought by their freedom fighters. The invaders were unprepared for losing the political power they enjoyed to wreak emotional havoc on the innocent people. They could not board the same train as the white people, and they had to embrace a nascent identity to secure some economic opportunities. In some extreme cases, they could not go to the same hospital as their white counterparts, and all of these have shaped the hostile minds they constructed. There is, therefore, the need to conduct some forms of political sanitation so that the negative areas would be successfully addressed.

Mbeki is aware that the most encouraging and greatly stimulating gift that people of his age and generation would achieve collectively was that they got the liberation that their succeeding generations could keep. Even when they did not see their predecessors’ horrible experiences, they would understand that they have done exceptionally well to take the country on the right trajectory. Liberation is related to their future because their economic and political future would be threatened without it. All of these prompted the people of Mbeki’s age to accept that attaining liberation was an enormous success associable with them. Thabo Mbeki understands that part of the challenges that consumed South Africa would become strictly corrosive if they had difficulty getting the assistance of other African countries in their quest for freedom.

When one is tormented, the possibility of being negatively affected by the situation will only be aggravated when individuals, acquaintances, and kindreds who would have persuaded and provided the moral support refuse to give their anticipated support. However, this was not the case with the other African countries. They stood solidly behind the country, imbuing the people with a spirit of perseverance and resistance, giving them the moral encouragement to continue. Due to the availability of supportive countries, victims of apartheid and political oppression were able to stand strong and weather the storms. It means that their freedom did not come on a platter of gold. They enjoyed the spirit of friendship, camaraderie and togetherness from other African countries, and since that combined voice produced a more audible agitation, the prospect of securing freedom became especially brighter. In all of this, the Thabo Mbeki generation made significant contributions across Africa.

Before the attainment of freedom and the foregrounding of South African politics to suit the contemporary realities of the people, it has often been imagined what the present generation of this great man would do in terms of handing over the baton of political leadership to the coming generation so that the latter would have a substantial impact in the enhancement of their freedom agenda that will cover all. However, Mbeki believes that the challenge confronting the country is a general one that leaves no one any comfort of reasons to isolate themselves in the struggle for freedom. He is convinced that the generation in place would have to understand that there lies a burden of responsibilities on them, which they cannot shy away from. No generation of freedom fighters has been called by individuals or groups to assign them the responsibility of taking over the course of justice for their people. They have always identified that their contributions are critical for continuing the struggles; thus, they take the bull by the horn. They would accept the challenges that come with it, and people would identify with them in no distant time.

Essentially, generations coming would have to demonstrate their readiness and begin to represent the voices of their people. There was pressure for change when they came into power. The people became agitated for a different reason this time around. They were concerned about the kind of leader they would erect in the new system that would send the message to the people that they had truly transitioned from the oppressive government. The Pan-African world is also concerned as it became clear that attaining freedom would pressure the African people to make the right decisions. Of course, at that moment, they had the moral right to drive the oppressive white government away, and in cases where they would not be that harsh, they could have changed the system to something that would torment and also pitch them against the imperialists. But they could make effective decisions governed by the desire to be fair to all. To avoid another round of problems was necessary so that they could enjoy a measure of peace and stability to continue with their lives. Even when critical decisions were made and necessary sacrifices were given, the reality of the contemporary South Africans continues to be dominated by the experience of long-term apartheid.

You must be logged in to post a comment.